One of the tragic side-effects of the politicization surrounding COVID-19, its origins, and the remarkably rapid development of vaccines aimed at preventing infection has been the resurgence of polio—another highly transmissible, devastating disease that was once close to eradication. In part, the vaccination campaign for polio was so successful that most people now, although they have heard of the disease, have never encountered anyone stricken by it. They have no idea just how terrible—and terrifying—it was in the days when it appeared to be both incurable and impossible to prevent.

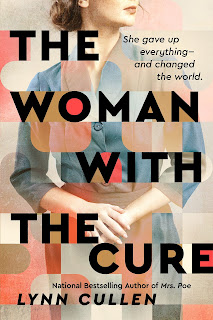

In my latest interview for the New Books Network, Lynn Cullen takes us back to that time in the 1940s when even the world’s most dedicated scientists did not know how polio moved through the body, how it was transmitted from one person to another, and how it wreaked so much havoc on vital organs. In particular, Cullen follows the career of one woman, Dorothy Horstmann, a doctor and medical researcher who devoted her life to finding out how polio worked and where intervention might be successful. She went on to apply the same skills to other illnesses, but only after she devoted more than twenty years to studying the disease known as infantile paralysis, although it did not only affect children. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was one notable example.

It’s a gripping tale, a fictionalized but mostly true story, and one particularly relevant to our time. So give the interview a listen, and then read the book.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

The essential contribution of this novel can be summarized in one sentence: like most of its future readers (I assume), I had never before heard of Dorothy Horstmann and her fundamental role in the research that led to the near-eradication of polio, despite having benefited hugely from her work. Throughout the 1940s, 1950s, and into the 1960s, she devoted her considerable talents and endless hours to tracking how polio spread throughout the body, but like the other remarkable women portrayed in this novel, she was forced because of her gender to play second fiddle to Doctors Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, her academic colleagues. Their contributions, of course, were also real and worthy of acclaim, but it was Dr. Horstmann—too often dismissed as “Dottie” or “Dot,” as if she were someone’s secretary—who made the crucial discovery that early in its path from the digestive to the nervous system, the polio virus created antibodies in the blood. That finding made the polio vaccine possible by defining an entry point for medical intervention.

Reading this novel has a particular resonance at this moment, when polio outbreaks are again affecting US cities because of vaccine hesitancy and the final eradication of the disease has been deterred in certain countries by political concerns—not to mention the COVID-19 pandemic, which has changed everyone’s experience of quarantine and disease. But I would like to emphasize that this is, first and foremost, a novel, centered on complex characters, a gripping plot, and the age-old battle between science and nature. I don’t know, for example, whether Dorothy’s love interest is a real person or the author’s way of contrasting the attractions of home with the pull exerted by fulfilling work. In the end, it doesn’t matter, because The Woman with the Cure works as a story, provoking questions about the choices its heroine makes and what we might do in similar circumstances—and that’s what counts.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Ideas, suggestions, comments? Write me a note. (Spam comments containing links will be deleted.)