The big news for this post is the release of Songs of Steppe & Forest 4, which I mentioned as imminent last week. On the surface, Song of the Sinner follows the star-crossed love affair of Anfim Fadeyev and Solomonida Sheremeteva, characters who have played bit parts in this series and its predecessor until now. But like most fiction, it also addresses a deeper problem: in this case, the belief held by so many women that a child’s needs are more important than a mother’s—or at least that a mother can satisfy her own needs or her child’s, but not both. The social difference between Anfim and Solomonida exists to spark this inner conflict, bringing it into the light so that it can be acknowledged, explored, and eventually resolved.

Of course, in our relatively liberal world, where money confers status and birth plays a role mostly as a marker for racial discrimination and multigenerational poverty, Anfim’s background (priest’s son, merchant, civil servant) may not seem so distant from Solomonida’s rank as the daughter of a noble clan. She has land and servants; he has cash and, increasingly, connections. Doesn’t that make them more or less equal—complementary, even?

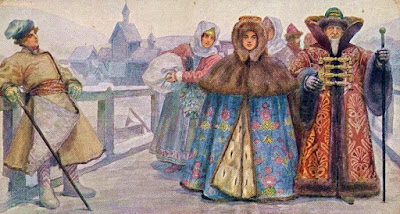

In sixteenth-century Europe, though, “blood” trumped money and skills every time. The language speaks for itself: blue blood, good blood, noble blood, royal blood—as if just being born into a family with a long genealogy could make a person clever or interesting or creative. So for Anfim and Solomonida, the difference in their station represents a real obstacle, one they must surmount, evade, or ignore. Their personalities and past experiences further ramp up the conflict. As the son of a priest, Anfim learned early to lie low and follow the rules, even when he’s on a quest to succeed. Solomonida married young to a man chosen by her father, a husband who looked good on the surface but proved vicious and uncaring toward those he considered beneath him. She survived and even escaped the worst of her husband’s excesses, but she fears giving anyone else that kind of power over her.

Moreover, when Solomonida and Anfim do—for reasons explained in the novel—realize that the costs of remaining mired in the past and constrained by society outweigh the benefits of breaking the rules, their decision has consequences, not all of them pleasant. Solomonida’s daughter feels betrayed; her cousin regards her as a loose and foolish woman and ramps up his plans for revenge; the noblewomen’s wives refuse to visit her in her new home, imperiling her efforts to find the right husband for her beloved child.

This novel is, at its heart, a romance, so in the end Solomonida and Anfim find a solution to their dilemma. In this novel, as in most romance novels, the driving question is not where the hero and heroine will end up but how they will get there, and which obstacles they will encounter along the way.

But their particular problem gets to the underlying heart of this series. In Legends of the Five Directions, every heroine—and every hero—married in what our ancestors considered the “proper” fashion: a spouse selected by the two sets of parents to fulfill specific economic or political goals of the family as a whole. But even in the sixteenth century, some people failed—or refused—to follow the rules. I set out in the new series to explore the escape routes available in every society, no matter how traditional. Juliana, in Song of the Siren, is a high-class courtesan; she married for a short time in search of security, but when her husband abandoned her, she left him without a second thought. She’s not looking for a replacement. Grusha lives as a single mother and supports herself and her son by working as a shaman, another traditional alternative for those whose gender identities or life choices deviated from the rigid categories that our ancestors defined as the norm. Darya toys with the idea of joining a woman’s monastery, which is the Christian version of an escape through religion. Her eventual rebellion, though, is to marry a man she loves—of her own rank and selected by her father but not someone who will satisfy the ambitions nurtured by the head of her clan. Solomonida’s tussle with her emotions, her unwanted realization that she has committed herself to someone of lower rank, could happen to anyone, married or single. But in her case she is also taking advantage of the greater freedom allowed to widows—first by avoiding remarriage altogether, then by going after a man whom many of her friends and relatives consider unsuitable.

Future books in the series will continue to explore the edges of this system. At the moment, I envision an interfaith marriage, a runaway bride, a cross-cultural union, and the sixteenth-century equivalent of a career woman who may not choose to start a family at all (although my heroines have a way of falling in love even when I expect them to do otherwise). Even in a past filled to the brim with kings and generals, abbots and cardinals, knights and their dutiful wives, we also find women warriors, queens and midwives, a female pope, and tradeswomen, physicians, and artisans of all varieties. Theirs are the stories I love to tell.

To find out more about Song of the Sinner, the best place to start is the dedicated book page on the Five Directions Press site. There you can find an audio excerpt, an online preview, a summary, and purchase links. Until Song of the Storyteller appears around this time next year, this new book is also featured on the home page at my own site. After that, you can find it on the series page, where the earlier novels are already listed.

Or just stay tuned, as I’ll be talking more about the new novel here as the weeks go by. It’s tremendous fun to release a new novel, but just getting it out doesn’t do much. What makes the whole experience of publishing worthwhile is helping a book find its readers!

Images: Song of the Sinner book cover © C. P. Lesley and Five Directions Press; Sergei Solomko, The Seventeenth Century, postcard ca. 1880, public domain via Wikimedia Commons; screen shot from Nomad: The Warrior (2005), dir. Sergei Bodrov.