On February 2, 1938—late at night, as was the custom—the Soviet police, then known as the NKVD, arrested a suspected German spy in Leningrad. Stalin’s Great Terror was well underway, meeting arbitrary targets set from the center the previous summer: 268,950 arrests, which should lead to 72,950 shootings and 196,000 prison sentences (8–10 years each) within four months. The specificity of the numbers is itself astonishing, not least because it emphasizes the state’s complete disinterest in the guilt or innocence of the accused.

In this case, the person arrested was Nina Anisimova, an acclaimed character dancer and budding choreographer at the Kirov Ballet. She was one of several dancers investigated for past contacts with one Evgeny Salomé, the legal consultant to the German consulate in Leningrad. Salomé, in turn, was a Soviet citizen of German extraction who appears to have been the kind of avid fan that Russians call a baletoman (ballet maniac). He liked to throw parties and invite the cultural elite of 1930s Leningrad, especially if they knew their way around a pointe shoe.

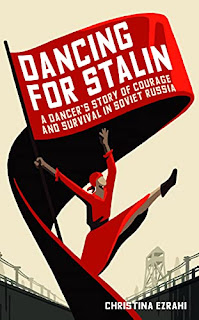

As Christina Ezrahi notes in her remarkable new book, Dancing for Stalin: A Dancer’s Story of Courage and Survival in Soviet Russia (London: Elliott & Thompson, 2021), there is no evidence that Salomé spied for the Germans. Still less is there any reason to suspect Anisimova of anything worse than knocking back a flute or two of champagne in the wrong company. She had even broken off contact with Salomé in 1934. But her arrest came during the height of persecution in Stalin’s Russia, and Anisimova spent months in detention, followed by a sentence of five years in a labor camp in Kazakhstan. She arrived at the transit camp in October 1938, after a nightmare journey aboard a cattle car, and narrowly escaped a further transit east.

So far, this is a tragic story but not, alas, an unusual one—as the records of the Memorial Society in St. Petersburg, so recently closed down on orders of the Russian government, make clear. But Anisimova’s story did not end there. Her husband, also an artist with the Kirov albeit not a dancer, bent heaven and earth to secure her release—risking his own life and freedom by lodging complaints at all levels of the political hierarchy. Seven months after Anisimova arrived in Kazakhstan—where, in a bizarre twist, she survived by dancing for her captors—her husband’s petition hit the right desk on the right day, and she was summoned back to Leningrad for a review of her sentence. By the end of September 1939, the NKVD had overturned her conviction, releasing her to return to the Kirov, where she continued to dance and to choreograph into her fifties (she was twenty-nine at the time of her arrest).

Life was not smooth sailing even then. In June 1941, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. The Kirov was evacuated to Perm (Molotov, in those days), and Anisimova went with them. But thanks to poor timing and perhaps other factors, her husband and sister stayed behind, narrowly surviving the Siege of Leningrad and the famine that made the winter of 1941 hideous.

Meanwhile, in Perm, Anisimova began work on the ballet Gayané, her greatest triumph—performed to music by Aram Khachaturian and a libretto by her husband. Russian troupes still dance it, although it has never established a foothold in the West.

In the decades that followed her rehabilitation, the two years that Anisimova spent in detention were erased from her record. Ezrahi learned of them only through an archival file that landed on her desk by mistake. From there she pieced the story together.

This is, however, more than the story of one courageous and wrongly accused woman and her steadfast, loving husband. Through Ezrahi’s fluid and captivating prose, readers learn about Anisimova’s suffering but also about the realities of the Gulag; the cynicism of the mass arrests and repression; the Kazakh famine (like the better-known Ukrainian Holodomor, the result of poor state planning and malicious neglect); Soviet prejudice against anyone with ties, however weak, to the previous regime; and much more.

Although we regret and deplore the death and suffering of millions, it is the nature of the human brain to react most strongly to the plight of individuals. This is why reading fiction builds empathy: it draws us into someone else’s emotional experience. The best histories have the same kind of impact. Dancing for Stalin is that kind of book, and even if you’ve never tackled academic history before, give it a try. You’ll be glad you did.

Image: Modern performance of Gayané, © Karen Yan, Own Work, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Ideas, suggestions, comments? Write me a note. (Spam comments containing links will be deleted.)