Yesterday I changed the water bottle in our garage cooler. This was a stretch for me, in part because the bottle is heavy but also because, in a family with two mechanically minded members, I am the outlier. I felt certain that if a way existed to spray water across the floor, the car, and myself, I would find it. But I was the only person around at the time, and it needed to be done, so after a bit of investigation I decided to tackle the problem.

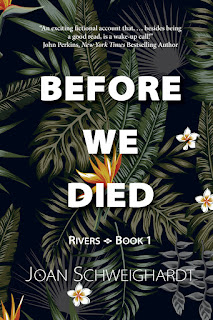

As things turned out, the process was simple enough that even I couldn’t mess it up, but it got me thinking about the demands that we as novelists impose on our characters. Except perhaps in a romantic comedy (where everything would go wrong, bringing hero and heroine together), reading about changing a water bottle, even one containing five gallons or so, would be a complete snore. Protagonists in novels have to surmount the kinds of obstacles that would cause most of us to run screaming for the hills. Just to cite a few examples published by Five Directions Press, plots can include an eighteen-year-old asked to defeat an ancient demon bent on destroying the humanity she once created (Gabrielle Mathieu, Girl of Fire); a sheltered sixteen-year-old girl confronting a known murderer intent on kidnapping two royal princes (my own Golden Lynx); and a pair of young men who embark on a voyage to the Amazon River in search of cash, only to endure a series of disasters that eliminates one member of their group after another (Joan Schweighardt, Before We Died).

So what is it with writers? Are we sadists in nerd clothing? “Psychologically distoybed,” in the words of West Side Story? Desperate for adventure but too wedded to our computers (and too isolated by nature) to seek it for ourselves?

Well, maybe some of the last. It is a great deal of fun to invent these extreme circumstances and throw oneself into imagining how a given character might cope with them. Channeling bad guys (and gals) is deliciously freeing too, so long as one can stash them away in their cages at the end of the day. And of course, one can never rule out hidden sadism or other forms of psychological disturbance. The general public probably already has its suspicions of people who claim to hear fictional beings chattering in their heads, even if those writers don’t themselves believe that the beings exist in any meaningful way.

But the real reason we torture our characters is simple: it makes for a good story. As readers, we get to sit back and watch, turn over potential responses in our minds, guess what the characters may do. We can live life in the fast lane without leaving our seats, and in doing so, we can explore emotions we hope never to experience: the yearning for revenge; the terror of facing a superior opponent; the moral quandary of balancing safety or reward against awareness of others’ needs or adherence to the social rules we were raised to respect. We can watch others make appallingly bad choices or rise to heroic heights we can only dream of reaching. In doing so, we prepare ourselves to face future crises. And no one is hurt in the process.

Or, to riff on Nancy Kress’s marvelous summary in her writing manual Dynamic Characters (“In life we want tranquillity; in our fiction we want an unholy mess, preferably getting unholier page by page” [159]), in life we want to worry about nothing worse than spilling water on the garage floor. In a novel, we want, if not murder and mayhem, at least an angry demon, a ruthless politician, or an environment filled with tarantulas, piranhas, and a jaguar or two. Much better to face such threats on the page than in real life!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Ideas, suggestions, comments? Write me a note. (Spam comments containing links will be deleted.)